Formative Years

Summers of my early childhood were spent on an island in the St. Lawrence River, where I fished almost every day. The best days, however, were the ones my father took me fishing, often with my mother and some of my siblings. Our summers focused on fishing jumbo perch, walleyes, smallmouth bass and many others. Our falls were dedicated to duck hunting in an era where my dad carved his decoys and taught me the lore of waterfowling.

We moved to a farm when I was eleven, and fishing opportunities changed dramatically from big water to farm-country creeks and slow-moving rivers.

Bullheads, rock bass, walleye, creek saugers, pike, and an endless variety of minnows or baitfish sustained my intense curiosity about fish and the places one finds them. The silt-laden creeks and small rivers were treasure troves of new fish species. I caught several varieties of suckers and other minnows, along with species not normally considered as game or panfish. These riverside adventures fostered a keen interest in biology, as I learned basics about where many local species lived, their spawning runs and life histories, and how to catch them. On the farm, snowshoe hare and grouse hunting, along with white-tailed deer, were added to my already formidable outdoor agenda.

These parallel paths of hunting, fishing and conservation were to follow me through the rest of my life. I became a fish and wildlife biologist (with a PhD in ecology), and began my career working on fish and other wildlife, as part of an environmental impact assessment, before joining the Canadian Wildlife Service in 1980. In mid-career, I left the federal government service to work with many organizations in Canada and the United States on behalf of fisheries and wildlife resources, habitat conservation, and the future of hunting and fishing.

Over 30 years ago, I began writing stories for outdoor magazines, capturing the outdoor experience in words and photographic images. I have credits in Ontario Fisherman, Outdoor Canada, Sentier Chasse et Peche (Quebec), and from almost the beginning, I became a field editor for Ontario Out of Doors magazine (OOD), where I joined a leading group of Canadian writers, anglers and hunters. I am currently the waterfowl columnist for OOD.

Editorial Debut: Breaking into the Line-Up

If I can’t fish for whatever reason, I can always write about it. Writing can be as addictive as fishing, and there never seems to be enough time to do either. I am fortunate that editors and readers enjoyed my stories and grateful for the opportunities to tell them on paper.

In the US, I have credits in In-Fisherman, Pederson’s Hunting, and for several years wrote a column called the Canadian Report for Wildfowl Magazine. I also have credits in Delta Waterfowl magazine, California Waterfowler and many other communications. Under the guidance of Carl Malz, I joined the masthead of Fishing Facts Magazine as a contributing editor. I was proud to see my work published alongside America’s legendary anglers at the time, like Carl Malz, Buck Perry, Roland Martin, Babe Winkleman, Spence Petros, Joe Bucher and many others.

Fishing Guide

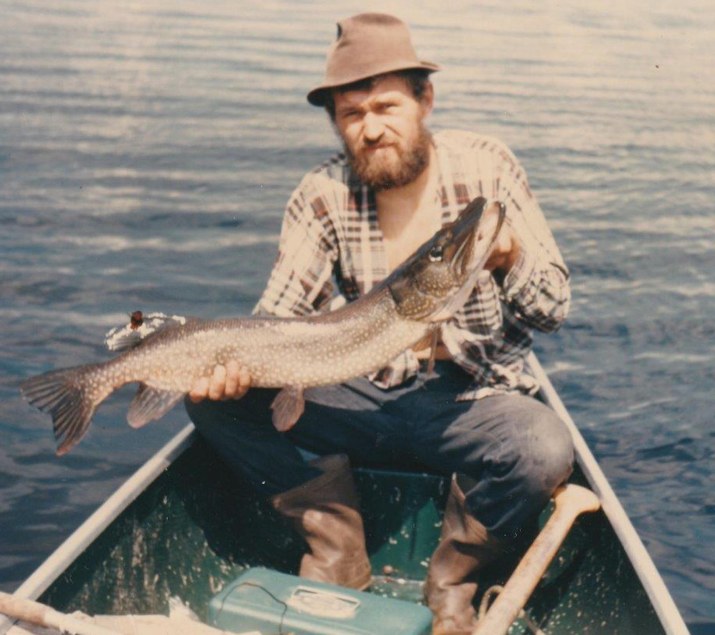

I worked as a full-time (seven days per week) fishing guide at O’Sullivan Lake Lodge, and occasionally on Stramond Lake in northern Quebec, from the beginning of May into September in 1968-69, and for a shorter time in 1970. These exclusive territories were part of huge land leases, with access to dozens of lakes and rivers. Most of my clients were from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and other states in the northeast and upper Midwest. I have guided sporadically, closer to home in Ontario over the years, particularly in pursuit of Lake Ontario salmonids, through their spring to fall migration around the basin. I still enjoy taking family, friends and a few outdoor writers fishing, and found that I could learn something about fishing from anglers at every skill level.

I am fortunate to have fished from the Yukon to Missouri, Louisiana, and into the Caribbean. Also on the east and west coasts of Canada, and from New Brunswick to the Florida Keys. Living in Manitoba and Saskatchewan for 14 years, I was privileged to experience some of the best walleye and northern pike fishing available anywhere, along with massive jumbo perch, burbot, and freshwater drum on occasion. As a multi-species angler, I have fished for many of the neglected species, including burbot, drum, catfish, white bass, grayling, whitefish, carp, gar, bowfin, sturgeon and in a bygone era, even American eels.

While remote northern fisheries are intriguing, this book is built on knowledge accrued over a lifetime of fishing mostly in populated areas that often entails many challenges related to human pressure on fish, and aquatic environments. It does take skill to catch fish in remote locations, but working the same waters that ordinary anglers’ fish, usually within an hour or so drive of where they live, is what “The Adaptive Angler” is all about. Skills learned close to home on pressured waters and savvy fish, are hard-won rewards for the adaptive angler.

Science

My science credentials feature an Honors B.Sc. in Agriculture from Macdonald College, the agricultural faculty of McGill University (Montreal). I remained there to complete a M.Sc. in Renewable Resources, and a Ph.D. in Ecology. The course work for my doctorate was completed as a visiting student at the University of Minnesota.

In my formative years as a scientist, I did all the things scientists were expected to do… field research, publishing scientific papers in peer-reviewed journals, attending conferences and symposia, and generally pushing back the boundaries to our understanding of the world and how it works.

Since then, I have used my scientific training to provide advice or oversight in the design of conservation policies, organizational programs and planning, fundraising, communications, environmental impact assessments, and many other projects. Wetland conservation was a key theme in my career, because of their ecological importance and vulnerability, positioned on the thin interface of land and water. Some of my work in wetland conservation involved providing the tools or training for wetland practitioners to make better decisions. This background, along with serving as a volunteer on the Continental Evaluation Team for the North American Waterfowl Management Plan (see below), introduced me to adaptive management. The genesis of “The Adaptive Angler” occurred when this new way of thinking (for me), combined with my work and fishing experiences, gradually emerged as a natural bridge from science to fishing strategy.

Armchair Science

As a scientist, I have always leaned toward the theoretical and speculative compared to the hard slogging of data acquisition and processing, although I have done my share of the latter. I am far more interested in ideas and how they might connect in the world of fish and fishing.

Theories are derived from ideas that have been tested over time and found to be resilient and predictable. One of my first delivered papers was “A Theoretical Approach to Problems in Waterfowl Management,” Published in: Transactions of the 46th North American Wildlife and Natural Resource Conference, 1981. Wildlife Management Institute. Washington. DC.”

All this to say that several of the learning opportunities in the book are based on “big picture” ideas and theories, that have been exposed to much thought and experimentation outside of the normal fisheries science domain. I am recommending selected ideas to anglers not only as fishing advice but as a good read for a blustery winter night, in the warm glow of a bright fire. The book is an opportunity for anglers to theorize (or some might say daydream) on concepts not normally considered in fishing, or the science relevant to fisheries management. But if we are to generate truly novel fishing ideas, we will need to seek them in new or different places.

Parallel Career Background

For several years I worked as a graduate student with the Delta Waterfowl Foundation, or as a practicing scientist while working as a population biologist for the Canadian Wildlife Service.

I have recounted my experience in the book, where I held the pen for Canada during the negotiation of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan. The Plan was a $1.5 billion conservation agreement signed between Canada and the United States, in May 1986. Mexico became a Plan partner in 1994. This Plan focuses on conserving wetlands for waterfowl, but it is also a major contributor to conserving wetlands vital to fisheries across the continent, in fresh and saltwater.

The Plan signing was the beginning of my exit from the federal government. I took an assignment as Executive Director of the Canadian Wildlife Federation’s National Recreational Fisheries Program, then became a consultant to the New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources and Energy, where I led the development of a new wildlife policy. I also served as scientific advisor to mitigate the potential environmental impacts of re-routing the Trans-Canada highway through a nationally significant wetland complex known as Grand Lake Meadows.

Observing the need for a national organization to represent the interests of anglers in fisheries conservation, I launched the Recreational Fisheries Institute of Canada and ran it as a registered charity for about five years. The institute was active in defending the National Recreational Fishing Survey in the early years, establishing a “Kid-Fish Canada” program to introduce kids to fishing and an agreement with Fish America Foundation to allocate partnership funding to fish habitat conservation projects, with the Institute in Canada. The Institute also completed one of the earliest reports on the potential impacts of climate change on recreational fisheries. The institute closed its doors after seven great years of conservation achievements across the country.

Returning to my career in consulting, I worked with IWMC-World Conservation Trust on behalf of a global consortium of groups supporting the sustainable use of wild resources. I edited their newsletter and served as an advocate for science-based sustainable use in forums such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

In the Year 2000, I rekindled a relationship with the Delta Waterfowl Foundation and became involved in almost all aspects of the organization, but particularly on issues related to the future of hunting, fish and wildlife-friendly landscape policy, and habitat conservation on a national scale.

Awards

I have not ever applied for nor chased recognition, but when you interact with this many people and organizations, across a vast country, sometimes the awards find you.

For several years I was an active member of the Outdoor Writers of Canada. As Vice-President, I helped organize national conferences and other business for OWC. I was presented the Pete McGillen award in 1999, in recognition of outstanding contributions to the aims of the Outdoor Writers of Canada.

I have received many accolades from grassroots organizations, comprising Canada’s Outdoor Network (which was not continued when I retired several years ago). Examples include the Rick Morgan Professional Conservation Award, for recognition of contributions to conservation, and the advancement of responsible hunting and angling in Ontario. I was also given a Canadian Outdoor Heritage Award for initiative in creating a dialogue among outdoor organizations across Canada. In 1992, I was appointed to the national Recreational Fisheries Award Selection Committee by the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada. For eight years on the “awards” committee I was able to help recognize volunteers working across the country, on behalf of sustainable recreational fisheries. I remain indebted to so many volunteers and organizations for their conservation and outdoor heritage efforts across the country.

With the future of hunting, fishing, trapping and gun ownership in Canada in clear jeopardy at the turn of the new millennium, I obtained support from Delta and other national stakeholders to establish Canada’s Outdoor Network, a national coalition of groups involved in sustainable use of fish and wildlife, conservation, gun ownership, and the major outdoor industry organizations, from manufacturers to retailers. Thirty organizations, from every province, plus the Yukon, participated in the network over five years. This national coalition included hundreds of thousands of organization members, their families and staff. It was one of the largest national grassroots advocacy groups ever founded in Canada. As Founder, Chair and National Coordinator, I helped the network identify emerging issues and set priorities. The network met via teleconference at least once per month. Major national issues were addressed jointly with all of the stakeholder groups participating equally in the process and resulting actions.

During those five years, the Outdoor Network’s grassroots constituency was able to defuse threats we identified and addressed through joint initiatives. Education, awareness and support for local actions across the country, were often sufficient to mitigate potential threats to our Canadian outdoor heritage.